Characteristics of commonly Used anxiety and depression scales and their rational application in general hospitals

Abstract

Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), 7-tiem Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ- 9), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) are commonly used scale tools for assessing anxiety and depression in clinic. Here the characteristics of these scales and their rational application in general hospitals were discussed. The aim of this review is to provide advice on the choice of anxiety and depression rating scales for non-psychiatrists/ psychologists in general hospitals.

Key words

anxiety; depression; Hamilton Anxiety Scale; Hamilton Depression Scale; 7-tiem Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; Patient Health Questionnaire-9; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Introduction

Anxiety and depression are both common mood disorders, which are negative emotions and subjective experiences of patients[1]. Anxiety is an emotion of worry, fear or over-concern about the present or future[2]. Depression is characterized by a significant and persistent low mood, even suicidal thoughts and behaviors[3-6]. At present, patients with anxiety and depression not only exist in mental and psychological hospitals, but also in general hospitals. Usually, there are two types of patients with anxiety and depression in general hospitals. One type is that anxiety and depression were caused by physical diseases[7], and there is a high rate of comorbidity ranging from 35.2% to 50%[8-10]. A study has shown that the incidences of anxiety and depression in inpatients were respectively 35.61% and 65.77% in non-psychiatric departments of general hospitals, which were significantly higher than the national norm[11]. Another type is that anxiety anddepression lead to somatization symptoms, which is the reason for patients’ visits[8,12]. Therefore, in general hospitals, the existence of anxiety and depression in patients often interferes with diagnosis, increases

difficulty of treatment, reduces treatment compliance, affects treatment effect and prognosis, and even worsens original diseases. All above could seriously affect recovery of chronic physical diseases. In addition, this type of patients prefer repeated visits,

which could increase their economic burden and cause waste of medical resources[13-16]. Therefore, doctors in general hospitals should possess the necessary ability of early identification, accurate diagnosis and rational treatment strategies on patients with anxiety and/or depression. The transition of the medical model from the “biomedical model” to the “bio-social-psychotic model” is imperative in general hospitals.

The appropriate use of simple and effective screening tools is an effective way to improve the recognition rate of anxiety and depression[17]. A variety of assessment

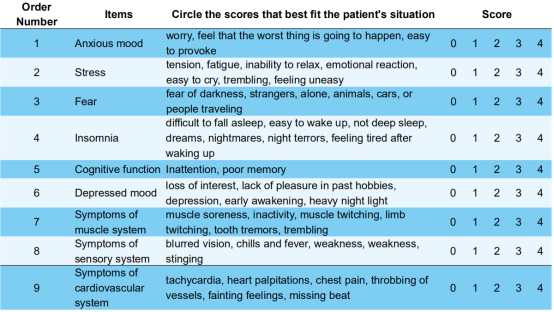

HAMA

HAMA introduction

HAMA was compiled by Hamilton in 1959[18]and revised into Chinese version by the National Scale Cooperation Group in 1986[19]. It is a classic anxiety rating scale used commonly in psychiatric clinic. There are 14 items in HAMA as shown in Table 1[20]. Except for scoring the item of behaviour performance during interview, the other items are scored according to patients’ oral narration and subjective experience. The total score of HAMA could well reflect the severity of anxiety. It is divided into 5 levels as follows: grade 0 (0 to 6 points) means no anxiety; grade 1 (7 to 13 points) means mild anxiety; grade 2 (14 to 20 points) means moderate anxiety; grade 3 (21 to 28 points) means severe anxiety; grade 4 (≥ 29 points) means extremely severe anxiety. In addition, HAMA can be divided into two subscales of physical anxiety and mental anxiety according to the characteristics of symptoms in each item[18]. The subscale of physical anxiety consists of 7 symptom items of muscle system, sensory system, cardiovascular system, respiratory system, gastrointestinal system, genitourinary system, and autonomic nervous system. The subscale of mental anxiety consists of 7 items including anxiety, stress, fear, insomnia, cognitive function, depressed mood, and behavior during interview.

Rational application of HAMA in general hospitals

Most of the anxiety scales are selfs rating scales, which could be affected to some extent by subjective factors. The scoring results might be distorted due to the inability of understanding well the professional terminology by patients. HAMA is a rating scale and relatively objective and accurate[21].Many researches have confirmed the reliability and validity of HAMA[22-24]. HAMA is a psychosomatic scale involving assessments of somatics (symptoms of different body systems), emotions (anxiety and depression) and behaviors. Another study showed that HAMA was more suitable for assessing functional anxiety and its severity in adult patients, rather than anxiety in various mental illnesses[23]. The above characteristics of HAMA suggest that it may be more suitable for using in general hospitals. There are two benefits of HAMA for non-psychiatrists/psychologists in general hospitals. First, the use of HAMA is reasonable because most patients in general hospitals have no history of mental illness. Second, the anxiety degree of patients can be assessed with HAMA. If anxiety is severe, doctors can quickly determine whether it is necessary to refer the patients to a mental and psychological specialist.

The clinicians who use HAMA must be trained strictly and possess some skills and experiences in diagnosing and treating mental illness. And the assessing proccess with HAMA takes a relatively long time. Accordingly it is difficult to use HAMA for nonpsychiatrists/psychologists unless they are helped by professional assessors. These limits the application of HAMA in general hospitals without a psychiatric department or psychiatrist/psychologist [24]. Moreover, the two subscales mentioned above are generically divided into physical anxiety and mental anxiety without different components describing anxiety or symptoms of body systems[25]. So the subscales are not be recommended to use in general hospitals where the symptoms of patients are usually various and the condition is complex.

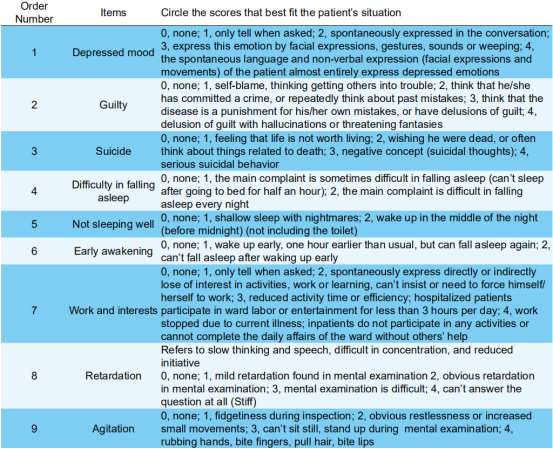

HAMD

HAMD introduction

HAMD was compiled by Hamilton in 1960. It is a classic depression rating scale widely used in clinic. There are 3 editions of 17, 21 and 24 items through multiple revisions[26,27]. The 24 items of HAMD are shown in Table 2. The 17 and 21-item editions consist of the items 1-17 and 1-21, respectively. Except for scoring the items 8, 9, and 11 during clinician-patient communication, the other items was scored according to the patient’s oral narration. And both are required in the item 1. The total score of HAMD could well reflect the severity of depression. Taking the 24- item scale as an example, the scoring criteria are as follows: 0-8, no depression; 9-20, mild depression; 21- 35, moderate depression; >35, severe depression[25,26]. Besides, according to the characteristics of symptoms in each item, HAMD can be divided into seven factors including anxiety/somatization, weight, cognitive impairment, day and night changes, retardation, sleep disorder and feeling of despair. The total scores of all items in each factor is named factor score. The facor scores can simply and distinctly reflect the characteristics of specific aspects in patients with depression simply and distinctly[28].

Table 2. Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD)[27]

Rational application of HAMD in general hospitals

HAMD can be used for the assessment of depressive symptoms in a variety of diseases including depression and bipolar disorder and anxiety, especially for depression[26]. It provides a scientific basis for diagnosis, treatment and research of clinical psychology[29,30].

However, similar to HAMA, HAMD is relatively time-consuming and labor-intensive, which limits its application in general hospitals without a psychiatric department or psychiatrist/psychologist. Furthermore, many studies have confirmed that there are overlapping symptoms between depression and anxiety[31,32], such as low mood, insomnia, decreased memory and impaired concentration[33,34]. Thus whether a patient is depressed or anxious, the assessment score of HAMD may be high.Under these conditions, depression and anxiety can not be identified well with HAMD.

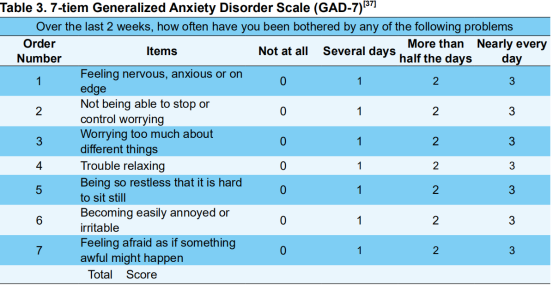

GAD-7 scale

GAD-7 scale introduction

GAD is one of the most common mental disorders[33], with a prevalence of about 1.5% to 2.8% in general hospitals in China[35, 36]. GAD-7 scale is a self-rating scale of GAD compiled by Spitzer in 2006 [37]. It consists of 7 items which are shown in Table 3. The scoring criteria of GAD-7 were as follows: 0 to 4 points are classified as no anxiety, 5 to 9 points as mild anxiety, 10 to 14 points as moderate anxiety, and 15 and above points as severe anxiety. The impairment of patient’s social function also can be assessed by inquirying the influence on life, work and interpersonal relationship.

If you find yourself having the above symptoms, how difficult have these symptoms made to your family life, work, and interpersonal relationship? Not difficult at all __ , somewhat difficult ____, very difficult ____, extremely difficult ____

Rational application of GAD-7 in general hospitals

GAD-7 is usually used to screen GAD and assess its severity[37], and also for other anxiety spectrum disorders such as panic disorder, social phobia and posttraumatic stress disorder [37-39]. GAD-7 is a patient self-rating scale which is concise, convenient and time-saving. Outpatients are easy to complete GAD- 7 by themselves in a short visit time, and help doctors quickly screen anxiety. These characteristics of GAD-7 indicate that it is suitable to use for doctors in general hospitals, especially non-psychiatrists/ psychologists[16,38,40]. GAD-7 has been used generally in multiple departments such as traditional chinese medicine clinic, cardiovascular clinic, psychology clnic and in-patient department in general hospitals[7,16,38,40-43]. The results of above domestic researches show that the reliability and validity of GAD-7 is good, and are consistent with the results of foreign studies[37,44]. These studies provide practical basis for diagnosis and treatment of psychosomatic diseases in general hospitals.

However, the assessment of anxiety is not comprehensive due to some characteristics of GAD- 7 including inadequate content about assessment of physical symptoms and short evaluation period (for the last 2 weeks). Moreover, since GAD-7 is a self-rating scale, the assessment results are inevitably affected by the education level and cognitive function of patients, and might not be as objective and accurate as the rating scale. Of course, GAD-7 is still widely used in general hospitals because of its good reliability and simplicity. It is recommended that medical staff properly provide non-inductive scale interpretation and fill-in guidance based on patients’ education level and comprehension ability.

In addition, GAD-7 needs to set the “optimal cutoff value (equilibrium demarcation point)”, which can balance the sensitivity and specificity of the scale and reduce the false positive/negative rates to the lowest[24]. Spitzer[37]thought that the sensitivity and specificity of GAD-7 was best when the cut-off value is 10 points. However, some factors from patients can influence on setting the optimal cut-off value, such as the patients’ family origin, social status, cultural differences, understanding ability and so on [43]. So the optimal cut-off value of 10 points might not be suitable for all patients, and needs adjustment depending on the patients’ situation. In some studies, the optimal cut-off values used by the clinicians of cardiovascular clinics, Chinese medicine clinics, psychology clinics and psychiatric clinics are 10, 6, 7, 12 points, respectively[38,42,43,45]. As the cut-off value increases, the specificity and positive predictive value increase, but the sensitivity and negative predictive value decrease[38]. A domestic study shows that when taking 3 points as a cut-off value, the sensitivity and specificity of GAD-7 were 100% and 33.0% respectively, suggesting that patients with negative scores could be excluded as GAD. When taking 15 points as a cut-off value, the sensitivity and specificity of GAD-7 were 27.3% and 100% respectively, suggesting that patients with positive scores could be diagnosed as GAD[46]. Therefore, the different optimal cut-off values of GAD- 7 are allowed to set in different departments of general hospitals according to their respective purposes of diagnosis and treatment.

PHQ-9

PHQ-9 introduction

PHQ-9 is a self-rating scale compiled based on the content of Major depressive disorder (MDD) in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)[47]. It is used to screen and diagnose five common dysfunctions including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders and somatization disorders. PHQ-9 consists of 9 items which are shown in Table 4. The scoring criteria of PHQ-9 for depression are as follows: 0-4, minimal; 5-9, mild; 10-14, moderate; 15-19, moderately severe; 20- 27, severe[48]. Notably, as long as the item 9 is positive, patients should be diagnosed with depression. The impairment of social function of patients also can be assessed by inquirying the influence on life, work and interpersonal relationship.

If you find yourself having the above symptoms, how difficult have these symptoms made to your family life, work, and interpersonal relationship? Not difficult at all ___, somewhat difficult ____, very difficult ____, extremely difficult ____

Rational applications of PHQ-9 in general hospitals

There are some defects of PHQ-9, including inadequate physical symptom assessment, short evaluation period, non-comprehensive assessment of depression, and lack of specific typing of depression[49]. Despite of these defects, PHQ-9 possesses the definite diagnostic value for depression, functions of assessment of depression severity and patients’ social function and provide a lot of informations for doctors to choose treatment plans[50]. PHQ-9 is short, economical, easy to understand and calculate. It also has good reliability and validity in many studies on inpatients (elderly and adolescents) in general hospitals and community[51-58]. The above characteristics of PHQ-9 show that it is suitable for doctors to use in general hospitals, especially for non-psychiatrists/psychologists. As PHQ-9 is a self-rating scale, it is recommended that medical staff properly provide non-inductive scale interpretation and fill-in guidance based on patients’ education level and comprehension ability.

Similar to GAD-7, PHQ-9 also needs to set the “optimal cut-off value”. In some studies, there are different cut-off values among different populations: the optimal cut-off value was 7 points in 1045 Chinese general population; 8 points in 582 inpatients in general hospitals; 11 points in adolescent populations[59]. Other studies showed that PHQ-9 has high sensitivity and specificity at 10 cut-off points[51, 60-62]. Collectively, PHQ-9 has good sensitivity and specificity at cut-off scores of 8-11[63].

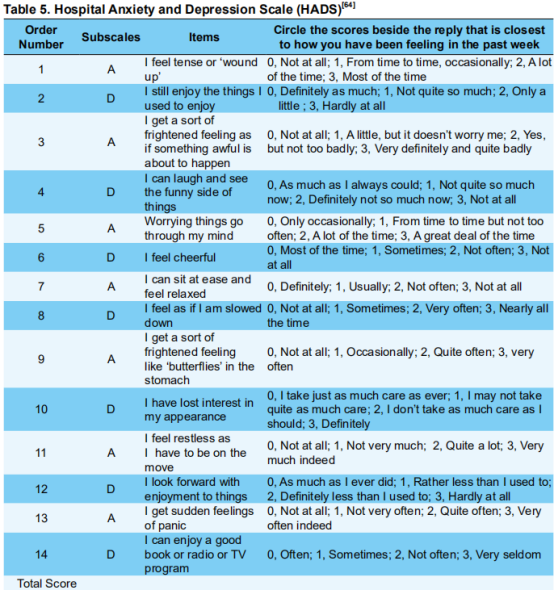

Note: Doctors are aware that emotions play an important part in most illnesses. If your doctor knows about these feelings he will be able to help you more. Don’t take too long over your replies: your immediate reaction to each item will probably be more accurate than a long thought out response.

HADS

HADS introduction

HADS is a self-rating scale compiled by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983[64]. It is mainly used for screening anxiety and depression in general hospitals[64, 65]. There are 14 items in HADS as shown in Table 5. Among them, 7 items constitute anxiety subscale (HAD-A) and the other 7 items consitute depression subscale (HAD-D). The scoring criteria of two subscales are as follows: 0 to 7 points is classified as no anxiety or depression; 8 to 10 points as suspicious anxiety or depression; 11 or more scores as definite anxiety or depression.

Rational application of HADS in general hospitals

As a screening scale, HADS can quickly assess patients’ anxiety and depression with good reliability and validity[66]. HADS meets the requirements for psychometrics and can be used as a good screening tool of anxiety and depression in general hospitals [65]. The difference between HADS and other scales is that the items about assessment of physical symptoms are eliminated. The purpose is to minimize the influence of overlap symptoms between physical diseases and emotional status and to effectively distinguish when anxiety/depression and physical diseases are comorbid. Meanwhile, the use of HADS is simple due to fewer items. Therefore, HADS has been considered to have more advantages in assessing anxiety and depression in general hospitals [24].

Although the comorbidity of physical diseases and anxiety/depression are common for patients in general hospitals, there are still many patients whose physical symptoms are mainly caused by anxiety and depression, namely somatic symptoms. If using HADS for assessment of patients with somatic symptoms, it is possible that doctors can not accurately judge if the patients' somatic symptoms are closely related to anxiety and depression. because of lack of the items about assessment of physical symptoms in HADS. This may lead to misdiagnosis of somatic symptoms. Therefore, we think that HADS can only be used in certain populations without physical symptoms. Furthermore, the item incompleteness of HADS limits the assessment of severity of anxiety and depression, so sometimes it is necessary to use HADS in combination with other scales[24]. In general hospitals, the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment of psychosomatic diseases might reduce when HADS is used by non-psychiatrists/ psychologists with insufficient experience on and the other 7 items consitute depression subscale (HAD-D). The scoring criteria of two subscales are as follows: 0 to 7 points is classified as no anxiety or depression; 8 to 10 points as suspicious anxiety or depression; 11 or more scores as definite anxiety or depression.

psychosomatic diseases. Thus HADS is more suitable to be used for quickly assessing the current emotional status of patients who have no physical symptoms or have been diagnosed with organic physical diseases.

Conclusion

With the transition of modern medicine from “biomedical model” to “bio-psycho-social medical model”, the psychological problems of patients are increasingly attracting attentions of medical staffs. Although there are higher visiting rates of patients with anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric departments in general hospitals, many problems about the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety and depression still arise because of the lack of experience of nonpsychiatrists/psychologists. For example, misdiagnosis, lack of experience of degree assessment, nonstandard treatment and poor treatment compliance of patients. Therefore, it is of great significance for use of a convenient, economic and accurate scale of anxiety and depression in general hospitals. HAMA, HAMD, GAD-7, PHQ-9 and HADS are used widely for assessment of anxiety and depression. They have been proven to have good reliability and validity. Among them, HAMA and HAMD are more comprehensive and thus should be used in priority in general hospitals with psychiatric departments. GAD-7 and PHQ-9 are self-rating scales, and can be completed independently by the patient. They are suitable to be popularized and applied in general hospitals without psychiatric departments and to be used in epidemiological investigations. HADS is more suitable for assessment of patients who have no physical symptoms or have been diagnosed with organic physical diseases. It is not recommended to be widely used for screening and diagnosing psychosomatic diseases in general hospitals.

References

- Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, et al. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019; doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(19)30934-1.

2. Wessman MM, Merikangas KR. The epidemiology of anxiety and panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 46(suppl): 11-17.

3. Li W. Research on anxiety and depression of neurology inpatients. J Qiqihar Univ Med 2014; 35: 1500-1501.

4. Ng CW, How CH, Ng YP. Depression in primary care: assessing suicide risk. Singapore Med J 2017; 58: 72-77.

5. He LL, Wang XJ. The spread of depression in China. Med & Philosophy 2012; 33: 29-31.

6. Zhang QF, Wang SJ. Psychological care for suicidal patients with depression. Guide of China Med 2011: (19): 55-57.

7. Lv LZ, Zhou YY, Su YS. The anxiety and depression status of inpatients in general hospitals analyzed by GAD-7 and PHQ-9. Modern Med J China 2017; 19: 47-49.

8. Yu N. Clinical analysis of somatic symptoms in patients with anxiety and depression. Shanxi Med J 2015; 44: 309-310.

9. Chinese Medical Association Neuropathy Branch Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of anxiety, depression and somatic symptoms in general hospitals. Chin J Neurol 2016; 49: 908- 917.

10. Kroenke K,Spitzer RL,Williams JBW,et a 1 . A n x i e t y d i s o r d e r s i n p r i m a r y c a r e : prevalence,impairment,comorbidity,and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 317-325.

11. Wang YF, Yang H, Zhang KR, et al. Analysis of anxiety and depression status and related factors in general hospital patients. China Med Industry 2005; 2: 28-29.

12. Wang WZ. Paying great attention to the diagnosis and treatment of somatic psychological disorders in internal medicine. Zhejiang Med J 2017; 56: 723-724.

13. Karasz A,Dowrick C,Byng R,et al. What we talk about when we talk about depression:doctor-patient conversations and treatment decision outcomes. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62; e55-63.

14. Yan LB. Survey of anxiety and depression in hospitalized patients in general hospitals. Med J Chin People's Health 2006; 18: 861-862.

15. Huang SW, Huang JR, Zhu XD, et al. Survey on inpatient with mixed anxiety and depressive disorders in comprehensive hospitals. J Modern Med Health 2015; 31: 360-362.

16. Feng YC, Liu N, Liu JX, et al. Using GAD-7 and PHQ-9 to investigate the anxiety and depression of hospitalized patients in general hospitals. J Qiqihar Univ Med 2015; 36: 4926-4927.

17. Lǒwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et a1. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004; 42: 1194-1201.

18. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32: 50-55.

19. Zhang ZJ. Behavioral Medicine Scale Manual. Beijing: China Medical Electronic Audio and Video Publishing House 2005: 215-229.

20. Jin Yu. Psychological measurement.Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2001: 171-203.

21. Sun D, Gao F, Chen JQ. Evaluation of Hamilton Anxiety Scale for Inpatients in Internal Medicine and Changes before and after Treatment. Acta Acad Med Xuzhou 2000; (04): 308-310.

22. Wang XD. Mental Health Rating Scale Manual. Chin Mental Health J 1993; 7(Supplement): 221 -223.

23. Tang YH. Hamilton Anxiety Scale. Chin Mental Health J 1999; (Supplement): 253-255.

24. Qu LM, Ye RF, Geng QS, et al. Comparison of three scales to detect anxiety in general hospital outpatients: HADS, SAS and HAMA. Chin J Behav Med Brain Science 2013; 22: 271-273. 25.

25. Wang C, Chu YM, Zhang YL, et al. Factorial structure of the Hamilton anxiety scale. J Clin Psychol Med 2011; 21: 299-301.

26. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23: 56-62.

27. Hamilton M. Development of a psychiatric rating scale for primary depression. Brit J Soc ClinPsychol 1967; 6: 278–296.

28. Gao Z, Jiang C, Liu QG. Factor scale characteristic of Hamilton depression scale of post-stroke depression in acute phase. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2003; 7: 728-729.

29. Helmreich I, Wagner S, Mergl R, et al. Sensitivity to changes during antidepressant treatment: a comparison of unidimensional subscales of the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) in patients with mild major, minor or subsyndromal depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012; 262: 291-304.

30. Wei JZ, Lv GQ, Shen KG. Analysis of factors affecting the treatment of patients with depression. J Clin Psychol Med 2012; 22: 190-191.

31. Viana AG, Rabian B. Fears of cognitive dyseontrol and publicly observable anxiety symptoms: depression predictors in moderate-to-high worriers. J Anxiety Disord 2009; 23: 1126-1131.

32. Drozdowskyj ES, Parajuá PG, Peláez C, et al.Comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder with mayor depression in primary care. Eur Psychiatry 2010; 25: 365.

33. Chinese Medical Association Psychiatric Branch. Classification and diagnostic criteria for mental disorders in China. 3rd edition. Jinan: Shandong Science and Technology Press, 2001.

34. Zhang LL, Ou HX.A comparative study of neurosis and depression with somatic symptoms and economic burdens. J Clin Psychol Med 2008, 18: 102-104.

35. Yan L, Zhang F, Liu ZN, et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among outpatients in general hospitals. Chin Mental Health J 2016; 26: 165-170.

36. Shi LL, Zhao XH, Jiang RH, et al. Occurrence of Depressive and/or Anxiety Disorders in Neurological Outpatients from General Hospitals in Beijing. Chin Mental Health J 2009; 23: 616- 620.

37. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092- 1097.

38. Wang L, Lu K, Wang CY, et al. Reliability and validity of GAD-2 and GAD-7 for anxiety screening in cardiovascular disease clinic. Sichuan Mental Health 2014; 27: 198-201.

39. Kroenke K,Spitzer RL,Williams JB,et a1. The patient health questionnaire somatic,anxiety,and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010; 32: 345-359.

40. Wang J, Dong Y, Wang HB, et al. Reliability and validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale in servicemen. Chin J Health Psychol 2017; 25: 733-736.

41. He SY, Li CB, Qian J, et al. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2010; 22: 200-203.

42. Zeng Q, He YL, Liu H, et al. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale in screening anxiety disorders in outpatients from traditional Chinese internal department. Chin Mental Health J 2013; 27: 163-168.

43. Qu S, Sheng L. Diagnostic test of screening generalized anxiety disorders in general hospital psychological department with GAD-7. Chin Mental Health J 2015; 29: 939-944.

44. Garcia-Campayo J, Zamorano E, Ruiz MA, et a1. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8: 8.

45. Donker T, van Straten A, Marks I, et a1. Quick and easy self-rating of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: validity of the Dutch web-based GAD-7, GAD-2 and GAD-SI. Psychiatry Res 2011; 188: 58-64.

46. Wang Y, Chen R, Zhang F. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale among inpatients in general hospital. J Clin Psychol Med 2018; 28: 168-171.

47. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIMEMD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999; 282: 1737-1744.

48. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ- 9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intem Med 2001; 16: 606-613.

49. Inoue T, Tanaka T, Nakagawa S, et a1. Utility and limitations of PHQ-9 in a clinic specializing in psychiatric care. BMC Psychiatry 2012: 12: 73.

50. Min BQ, Zhou AH, Liang F. Clinical application of Patient Health Questionnaire for self-administered measurement (PHQ-9) as screening tool for depression. J Neurosci Mental Health 2013; 13: 569-572.

51. Hu XC, Zhang YL, Liang W, et al. Reliability and validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 in Chinese adolescents. Sichuan Mental Health 2014: 27: 357-360.

52. Kiely KM, Butterworth P, Validation of four measures of mental health against depression and generalized anxiety in a community based sample. Psychiatry Res 2015; 225: 291-298.

53.Beard C, Hsu KJ, Rifkin LS, et al. Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. J Affect Disord 2016; 193: 267-273.

54. Hinz A, Mehnert A, Kocalevent RD, et al. Assessment of depression severity with the PHQ- 9 in cancer patients and in the general population. BMC Paychuatry 2016; 16: 1-8.

55. Chen R, Wang Y, Yu JY, et al. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in general hospital inpatients. Sichuan Mental Health 2017; 30: 149-153.

56. Xu Y, Wu HS, Xu YF. The reliability and validity of patient health questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9) in Chinese elderly. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2007; 19: 257-259,276.

57. Liu ZW, Yu M, Hu M, et al. PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 for screening depression in Chinese rural elderly. PLoS One 2016; 11: 1-10.

58. Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014; 36: 539- 544.

59. Ganguly S, Samanta M, Roy P, et a1. Patient health questionnaire-9 as all effective tool for screening of depression among Indian adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52: 546-551.

60. Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Afolabi OO. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. J Affect Disord 2006, 96: 89-93.

61. Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry 2008; 8: 46.

62. Bian CD, He SY. The reliability and validity of a modified patient health questionnaire for screening depressive syndrome in general hospital outpatients. J Tongji Univ (Medical Science) 2009: 30: 136-140.

63. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012; 184: 191-196.

64. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361-370.

65. Sun ZX, Liu HX, Jiao LY, et al. Reliability and validity of hospital anxiety and depression scale. Chin J Clinicians (Electronic Edition) 2017; 11: 198-201.

66. Zheng LL, Li HC. Rating scales for anxiety and depression. Chin J General Practitioners 2016; 15: 334-336.

67. Le X, Zhao TY, Kuang W. Advances in research on preoperative anxiety assessment scale. J Nursing 2017; 24: 26-30.

68. Fan Q, Ji JL, Xiao ZP, et al. Application of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) among medical outpatients. Chin Mental Health J 2010; 24: 325-328.